By Michele Straube for EDR Blog.org

Maybe, maybe not … but if not, our brains are easily re-wired to cooperate.

I recently participated in a panel discussion on Group Decision-Making as part of the Symposium on Science & Literature, co-sponsored (cooperatively, of course) by multiple University of Utah departments; the symposium co-directors came from Mathematics and English.

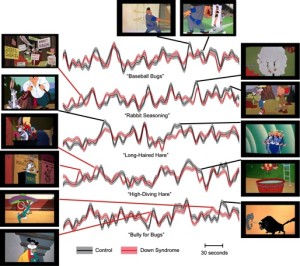

Jeffrey Anderson, MD, PhD, Assistant Professor in the Interdepartmental Program in Neuroscience at the University of Utah, kicked the panel off with a talk entitled “Bugs Bunny, Zen, and the Art of Conflict.” Dr. Anderson suggested that human brains have strong instinctual mechanisms to recognize and attend to conflict and imminent harm. He cited to research in which the high-conflict scenes in cartoons (e.g., Bugs Bunny) caused increased brain activity, while other scenes did not.

This makes some sense. If a bear or tiger comes running after us, we want our brains to be able to focus exclusively on that imminent danger. In that situation, “fight or flight” is exactly what we need our brains to be thinking about. But not every conflict situation is quite that life-threatening. Dr. Anderson asserted that, with practice, our brains can and do re-wire that immediate response to conflict and strengthen neural pathways that can help us think rationally and work cooperatively. He cited to research on Zen masters in meditation whose brains showed changes in blood flow away from the “fight or flight” centers of the brain during meditation.

My panel topic, following directly after Dr. Anderson’s neuroscience primer, focused on the “power of consensus” as a process that helps individuals in conflict reorient their focus on possibilities, rather than getting stuck in disagreement. Consensus, as I think about it, has three components – it is a product, it is a process, it becomes a way of being.

Consensus, thought of as a noun, is the outcome of negotiation, collaboration or dialogue. When all the participants in a disagreement find a solution they can live with and are willing to implement, consensus has been reached. In the collaborative groups that I facilitate, we know we have consensus when all participants show a thumbs-up or thumbs-sideways about a particular solution. If we have one or more thumbs-down, we continue to use consensus as a verb.

The process of consensus-building, again as I practice it, is a way of helping the brain refocus away from unproductive conflict to constructive dialogue. Disagreement is valuable, but all participants in a collaborative effort share the responsibility to identify potential solutions that can meet everyone’s needs. In other words, no individual participant has absolute veto power. As long as there are differing opinions that prevent everyone from being comfortable with the options on the negotiating table, the conversation about other possibilities continues, often prompted by questions like “why does that option not work for you?” or “what would we need to change to make it work for you?” This approach to consensus-building requires all participants to listen actively to each other, to understand what really matters for themselves and the other participants, and to think creatively about how all needs might be met.

Finally, the active listening and creative problem-solving encouraged through the process of consensus-building often is internalized by the individual participants and becomes their habit of how to handle other conflicts. One collaboration member recently told me that consensus-building has become his “way of being” after seeing its high rate of success.

One of the keynote speakers at the Symposium on Science & Literature was Thomas Seeley, Professor in the Department of Neurobiology and Behavior at Cornell University, who studies the collective decision-making of honeybees. Imagine my surprise when I learned that honeybees use the power of consensus to reach the “best” decision for the group! Decisions about whether and when to move a hive are made based on a group “discussion” about all possible options and an evaluation of their pro’s and con’s until it becomes clear to the group which decision will work best for all.

Are we wired to cooperate? Maybe that’s the wrong question. Sounds like it’s in our control and we can choose whether to cooperate or stay in conflict.

Michele Straube is Director of the Environmental Dispute Resolution Program in the Wallace Stegner Center for Land, Resources and the Environment at the S.J. Quinney College of Law, University of Utah. She is fascinated by the role of neuroscience in conflict.