By Brian Flach

“Science is not a boy’s game, it’s not a girl’s game. It’s everyone’s game.”

Growing up, I was raised with the belief that you should be judged by your talent and accomplishments. I was taught that everyone should be given the opportunity to prove themselves and further themselves based on the quality of their work. In engineering, I was taught that there was a beautiful purity where the laws of science governed. Science did not discriminate. It did not care what you looked like. It was blind to everything but your intellect and your effort. The engineers themselves were a different story, however, and it seems as though Congress has noticed.

On March 27th, the U.S. House Subcommittee on Courts, Intellectual Property, and the Internet convened a panel to discuss a recent U.S. Patent and Trademark Office Report. (https://judiciary.house.gov/legislation/hearings/lost-einsteins-lack-diversity-patent-inventorship-and-impact-america-s). The report, “Progress and Potential: A profile of women inventors on U.S. patents,” investigated the trends in female inventors named on U.S. patents from 1976 to 2016. (https://www.uspto.gov/learning-and-resources/ip-policy/economic-research/progress-potential). The report disclosed some shocking information, such as the fact that only 4 percent of all issued patents in the last decade were created by all-female teams or solo inventors. Since it warranted a panel within a month and a half of its publishing, we can see that this report, and its implications, are of particular interest to Congress.

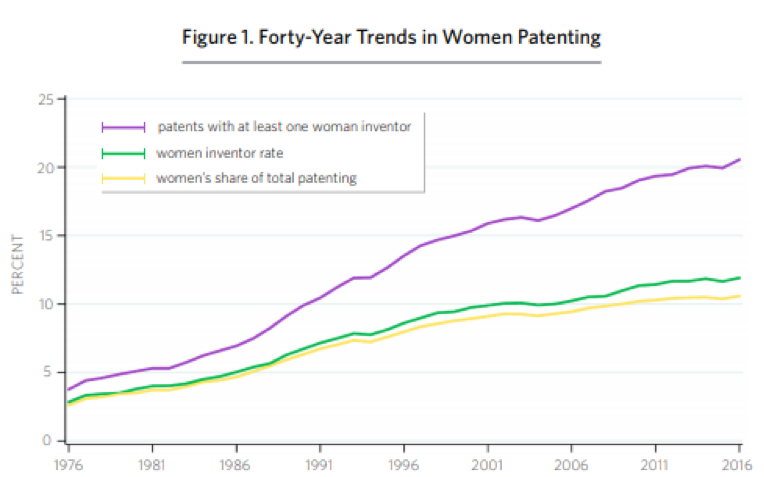

The report shows that since 1976, the women inventor rate, women’s share of total patenting, and number of patents with at least one female inventor have drastically increased. (https://www.uspto.gov/sites/default/files/documents/Progress-and-Potential.pdf). The share of patents that include at least one female inventor in particular has tripled, growing from 7 percent in the 1980s to 21 percent by 2016. Id. However, the report teaches how these surface numbers are also misleading. The report explicitly discusses how “Notable differences in the number of male and female patent inventors persist despite greater female participation in science and engineering occupations and entrepreneurship.” Id.

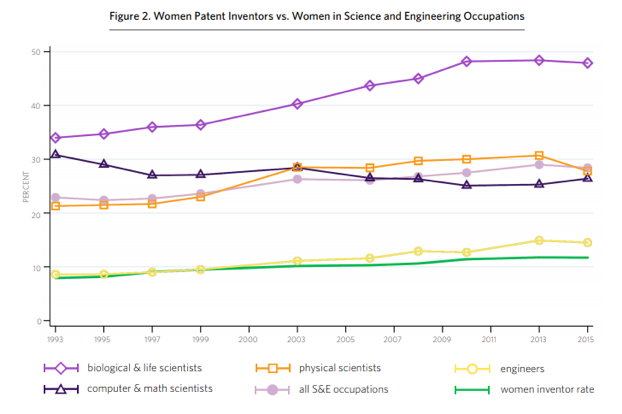

This is most clearly evidenced by the disparity between women’s inventor rates in comparison to women’s share of science and engineering jobs. As seen in the table below, there has been a consistent disparity between the number of women in science and engineering fields and female inventors. In 2015, this disparity was as large as 16 percent. Engineering is the only field where workforce participation has consistently aligned with inventor rate.

Overall, the report paints a picture of growth and improvement with significant strides yet to be made. It both points out a consistent growth in participation and inventorship while drawing attention to the disparity between them. It singles out industries in which inventor rates are at their lowest, particularly biotech and mechanical engineering. And most importantly, it provides us with ideas of how to further this development and close the gap in this disparity. For example, the report indicates that multi-gender research teams, fostering developments in technology-rich areas, and expanding women into previously male-dominated fields are some ways in which this gap might be bridged. The larger, gender-mixed inventor team approach in particular is supported by the report as a particularly effective method of increasing female inventorship. While not a solution to the shockingly low numbers of solely female inventor teams, it’s a start to ensure that so many essential voices are being heard.

I have been the lab partner and co-worker to many female scientists and engineers. I have seen brilliant ideas flow like a river in countless conversations and presentations. From developing new microparticle biosensors to designing the HVAC systems we rely upon daily, these women have used their degrees to further science and industry in countless ways. And yet, as shown in this report, so many are still not heard. So many ideas are lost. As the panel’s title suggests, so many potential Einsteins are never discovered. These inventors deserve a voice and a chance to patent their work. Not because they’re women, but because they’re people. Scientists. Engineers. Inventors. Creators. And just like any other inventor, their creations deserve a chance at life. A chance to benefit those around us. As Marie Curie once said, “[T]he way of progress [is] neither swift nor easy.” However, this report and the resulting panel suggest that we’re on a path of progress, a path of equality, and a path of inventorship. Because in the words of Nichelle Nichols, “Science is not a boy’s game, it’s not a girl’s game. It’s everyone’s game.”

Brian Flach

Brian is a third-year law student at the S.J. Quinney College of Law. He graduated from the University of Utah with an Honors B.S. in Biomedical Engineering and worked as a research assistant in the Mario Capecchi Laboratory. Over the course of his law school career, Brian has served as a legal intern at BioFire Defense, L.L.C., a summer clerk at Thorpe North & Western, and as a fellow for the American Society of Pharmacy Law. This year, he is excited to serve a judicial clinic under Justice Constandinos Himonas of the Utah Supreme Court.