By Mary Dumas for EDRBlog.org

Complexity and conflict can interfere with our ability to listen accurately and sustain focused attention when serving as a mediator or engaging in a collaboration endeavor. However, mindfulness principles and practices help mediators, innovators and collaboration participants by increasing awareness of changing conditions and sharpening focused attention during the creation of shared knowledge, organizational learning and strategic change.

As a mediator for science-informed policy and community improvement initiatives, I’ve applied principles of mindfulness to help groups and organizations refresh their perspective and expand their awareness of potential mutual gains, achievable through collaboration.

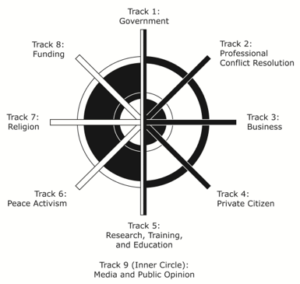

Some applications are structural, such as a whole-of-society engagement framework (see Figure 1) to build broad awareness of the complex system in which the collaboration is occurring.

The other type of mindfulness intervention I apply is behavioral. Participants can expect to test key concepts, discuss new learning with others, and produce plain language texts to support continued learning for those engaged in the future. Experiential learning and discernment activities are integrated into project schedules and meeting agendas in order to link knowledge creation and organizational learning, as described in Barry Sugarman’s, “Learning- based Approach to Organizational Change” (Sugarman 2000).

What is mindfulness?

The first principle of mindfulness is open awareness, a non-judgmental attentiveness to what is happening now, moment by moment.

The second principle of mindfulness is focused awareness or the practice of discerning awareness; there are two parts to it:

- First, focus on awareness of our internal state of being.

- Second, focus on awareness and discernment of external conditions and possible responses.

How does one engage in these distinct modes of awareness? Mindfulness is the awareness of things as they are, changing dynamically, inside our own sense and the world around us. “Mindfulness is the very simple process of actively noticing new things. When you actively notice new things that puts you in the present, makes you sensitive to context. And as you notice new things it is engaging and it turns out, after a lot of research, that we find that it’s literally, not just figuratively, enlivening,” as researcher Ellen Langer defines it (Langer 2017).

Get notified when new articles are posted to the EDR blog – sign up for our email list »

One approach is to maintain a frank, direct awareness in all parts of daily life, no particular faith required, as Langer describes. Another approach is to adopt a regular mindfulness practice, such as the Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction (MBSR), popularized and researched through the health community, or a contemplative tradition from your faith. For example, H.H. Dalai Lama suggests, “when dealing with strong feelings arising, consider that the nature of the view is exaggerated, the target is specific, solid. When strong feelings arise dissect and analyze to diffuse the nature of the emotion. With practice we can support awareness and distinction of mental factors. Overtime, concentration in mindfulness or meditation practice is to equalize self and others by developing altruism and compassion in the face of prejudice” (H.H. Dalai Lama 2005).

How can mindfulness help in collaboration initiatives?

Collaboration partners enter a messy inter-disciplinary and inter-cultural world. Complexity builds quickly as differing disciplines, lived experiences and perspectives merge with technical information and procedural details. Even with the best of planning, design and resources, our human condition or neurobiology sets the pace for listening and learning. “We are continually scanning our environment for threats via neuroception. We enter Stage 2, the sympathetic-adrenal system, when a threat is detected. When a threat is not detected and we feel secure, the social engagement system is activated; the stress response is inhibited and the cranial nerves are activated to promote engagement” (D. Rahal 2017).

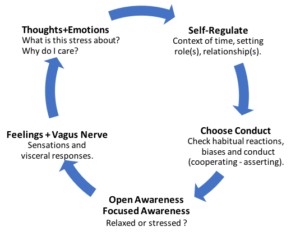

I apply mindfulness through open awareness and regularly (10-15 minute) scan the nonverbal behavior and stress state (mine and tone of room) for emerging needs, patterns, and a pace that works well for the group. I also apply a discernment practice at the negotiation table as an ongoing investigation of the many layers of experience taking place, for me and the participants (see Figure 2).

Surfing the tensions of complexity and stress

Collaboration groups gain new knowledge through a series of productive, whilst sometimes tedious exchanges of technical rigor and hard truths. Stress is a signal to focus and get creative!

Discerning awareness practices help name and bring context to what is happening, as well as shift focus to other aspects of the situation. Helpful refocusing interventions include:

- Add reflection tasks to the agenda to promote listening and learning, it norms the act of pausing and integrating new information (see Figure 1).

- Balance the task and process-oriented discussions to regulate pace of the group’s emotional and cognitive work (see Figure 2).

- Encourage discovery and awareness of what is happening now versus what was planned or projected.

- Use Figure 1 and Figure 2 frameworks to conduct a rapid analysis of incremental changes.

- Add common goals to agendas and dissenting opinions and outlier ideas to summaries so task orientation does not override new learning.

Neuroscience and brain research institutes in the U.S. have found that direct mindfulness and contemplative practices can improve self-awareness and distinction of mental factors impacting stress resilience and learning. Beginner meditators showed improved ability to regulate attention and executive brain function, including “orientating attention, monitoring conflict, and inhibiting emotionally charged but irrelevant information” (Mind and Life Education Research Network 2012 ). Changes were found in regulation of emotion and attention, higher self-awareness of conduct (verbal, micro and macro expressions) — all of which are core competencies for mediators, facilitators and innovators.

As a young student in the 1980s, I had the good fortune to be introduced to many Tibetan Khenpos and monks who came to the U.S. to share the Tibetan mental development methods. These sitting and moving meditation practices improved my concentration during day-long facilitations. There is a natural affinity between meditation and mediation, in their unity we seek the middle way to disentangle conflicts, with the goal of evolving our view to include that which we had not formerly noticed or known.

Over time, mindfulness practices cultivate a more relaxed, open presence — raising awareness of my own patterns and shifts, that enables me to more readily extend a hopeful, kinder outlook with others who I might be struggling with momentarily, or persistently!

Mary Dumas, President, Dumas & Associates, Inc. is an independent conflict dispute resolution professional with over three decades of experience working with private organizations, governments, tribes, public agencies, universities, faith communities, nonprofits and research institutes. Mary is known for designing employee and stakeholder engagement programs that translate technical information and regulatory mandates into accessible, collaborative processes and actionable plans with impact and legacy. Contact information: mary@dumas-assoc.com; www.dumas-assoc.com; 360-966-8865.

Mary Dumas, President, Dumas & Associates, Inc. is an independent conflict dispute resolution professional with over three decades of experience working with private organizations, governments, tribes, public agencies, universities, faith communities, nonprofits and research institutes. Mary is known for designing employee and stakeholder engagement programs that translate technical information and regulatory mandates into accessible, collaborative processes and actionable plans with impact and legacy. Contact information: mary@dumas-assoc.com; www.dumas-assoc.com; 360-966-8865.