By Kelsey Kahn for EDRblog.org.

Background

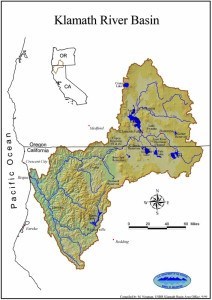

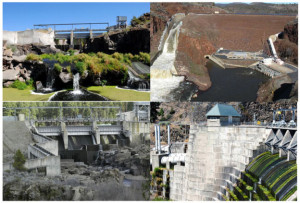

Straddling the Oregon-California border, the Klamath Basin is home to the PacifiCorp-owned Klamath Hydroelectric Project; six power-generating dams along the Klamath River. Four of these dams are over 50 years old and out of compliance with the Endangered Species Act. [3] They each require costly retrofits because they inhibit the recovery of three threatened species: the Lost River and Shortnose suckers, and Coho salmon. [4] PacifiCorp determined that it was more cost effective to deconstruct the dams with monetary support from the federal government and the state of California than to retrofit or remove the dams themselves. However, PacifiCorp’s decision did not sit well with all constituents in the Basin. This was no surprise considering the region’s history of water rights allocation disputes. [5] In response to the company’s proposed plan, over 40 stakeholders comprised of native Tribe members, farmers, ranchers, and environmentalists of all stripes came together to address the complex technical, social, political, cultural and environmental ramifications from dam removal. [6] Two Settlement Agreements were reached.

National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA)

Used in cases like this, NEPA provides a procedural framework for agencies to assess the environmental effects of their actions. Intended to open communication channels between relevant parties and federal agencies, it gives both citizens and scientists an avenue to learn about and critique decision-makers’ actions. [7] Unfortunately, it has one unforgivable flaw: it does not incorporate the opinions of stakeholders as much as it relies on the findings of science-based studies. In its current state, the NEPA process keeps stakeholders from dealing directly with the political ramifications of environmental solutions and precludes certain options by focusing debates squarely on procedural science.

To be notified when new EDR blog articles are posted, please sign up for our listserv »

The most important step of the NEPA process is defining the “Purpose and Need” statement. This short paragraph is intended to identify the main goal of federal government action and shapes the rest of the process. Written by top-tier scientists and policy analysts before they performed a myriad of scientific studies, the Purpose and Need statement for the Klamath proceedings identified the objective of restoring salmonid species. [8] However, a more in-depth understanding of the region’s history of disputed water allocation makes it clear that the recovery of salmonid species, while important to the region, far from encompasses all of the issues associated with dam removal. Although the final NEPA Environmental Impact Statement recommends dam removal as the best way to reach the fish restoration goal, the use of habitat restoration is a way of, either intentionally or unintentionally, silencing the needs of other stakeholders.

The NEPA model inherently emphasizes the importance of natural sciences in a social science landscape. This enables those in power to put their desires above those that are directly affected by the action and uses scientific facts to back up their claims. In the Klamath example, the dams only have to come down because the NEPA process goal of restoring salmonid species. This argument is not intended to say that salmonid species are not important; they are hugely relevant actors in this controversy. But they should be seen as one group of actors among many and should be used more as a way to bring everyone to the table instead of being the focus of the debate.

NEPA should be reimagined in a similar light, as a flexible framework intended to engage and inform the public not as a defined procedure that occurs, sometimes, despite public involvement. Why, for example, couldn’t the Purpose and Need statement draw more heavily from the non-NEPA Settlement Agreements where the desires of many more parties were aired?

NEPA emerged from legal and political systems that rely heavily on fact and science, which makes it no surprise that it does the same. But it does not have to stay that way. The Settlement Agreements organized in the Klamath Controversy are a good example of a different approach to the issue: negotiation instead of litigation. If we can work to incorporate messy and complicated negotiations like the Settlement Agreements into the NEPA process, it will enable groups who have been historically neglected in environmental debates to have more of a say than just submitting comments and appealing final NEPA rulings.

Kelsey Kahn is a recent graduate of Lewis & Clark College with a degree in Environmental Studies. During her time in Portland, Oregon, she completed an honors thesis titled “Whiskey’s for Drinkin’ Water’s for Fighting’: Science Politics and Dam Deconstruction in the Klamath Basin.” She currently works for the Green Energy Institute at Lewis & Clark Law School and is making the move to New York City in the coming months.

Kelsey Kahn is a recent graduate of Lewis & Clark College with a degree in Environmental Studies. During her time in Portland, Oregon, she completed an honors thesis titled “Whiskey’s for Drinkin’ Water’s for Fighting’: Science Politics and Dam Deconstruction in the Klamath Basin.” She currently works for the Green Energy Institute at Lewis & Clark Law School and is making the move to New York City in the coming months.

For more information and to check out my full thesis and research, visit my website: https://ds.lclark.edu/kkahn/thesis-landing-page/

Works Cited

Blumm, Michael, and Andrew Erickson. 2012. “Dam Removal in the Pacific Northwest.” HeinOnline 42 Envtl. L. 1043 2012 (July).

Council on Environmental Quality. 2007. “A Citizen’s Guide to the NEPA: Having Your Voice Heard.” Executive Office of the President. http://www.blm.gov/style/medialib/blm/nm/programs/planning/planning_docs.Par.53208.File.dat/A_Citizens_Guide_to_NEPA.pdf.

Powers, Kyna, Pamela Baldwin, Eugene H. Buck, and Betsy A. Cody. 2005. Klamath River Basin Issues and Activities: An Overview. CRS Report for Congress.

Summary of the Klamath Basin Settlement Agreements. 2010. Klamath Basin Coordinating Council.

U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, U.S. Bureau of Land Management, and U.S. Geological Survey. 2013. Environmental Impact Statement for the Klamath Hydroelectric Settlement Agreement. Environmental Impact Statement. U.S. Department of the Interior. http://klamathrestoration.gov/sites/klamathrestoration.gov/files/Additonal%20Files%20/1/Executive%20Summary.pdf.

[1] Map courtesy of the Bureau of Reclamation, http://www.usbr.gov/mp/kbao/maps/1_basin.jpg

[2] Images courtesy of Oregon Live http://media.oregonlive.com/environment_impact/photo/klamathdam-9jpg-ff49983fdd232b35.jpg, http://media.portland.indymedia.org/images/2007/03/356578.jpg, http://images.nationalgeographic.com/wpf/media-live/photos/000/371/cache/klamath-river-dams-could-be-removed-freshwater_37188_990x742.jpg, http://blog.oregonlive.com/news_impact/2008/11/jcboyle.JPG

[3] Blumm, Michael, and Andrew Erickson. 2012. “Dam Removal in the Pacific Northwest” (July 6).

[4] Powers, Kyna, Pamela Baldwin, Eugene H. Buck, and Betsy A. Cody. Klamath River Basin Issues and Activities: An Overview. CRS Report for Congress, September 22, 2005.

[5] Powers et. al, 2005..

[6] “Summary of the Klamath Basin Settlement Agreements.” 2010. Klamath Basin Coordinating Council.

[7] Council on Environmental Quality. “A Citizen’s Guide to the NEPA: Having Your Voice Heard.” Executive Office of the President, December 2007.

[8] U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, U.S. Bureau of Land Management, and U.S. Geological Survey. Environmental Impact Statement for the Klamath Hydroelectric Settlement Agreement. Environmental Impact Statement. U.S. Department of the Interior, April 4, 2013.